April 01, 2024

The Resurgence of Fiber Art

These days, it seems the world can’t get enough of fiber arts. And thank goodness! I can’t help but see it as a timely antidote to a screen-filled world. How lovely it is to see people crocheting on public transport to fill the time—or learning to sew their own clothes. Fiber arts are accessible, therapeutic in their tactile simplicity, and incredibly useful to add to your skill set!

But it’s also for these humble reasons that historically, the art world hasn’t exactly donned an attitude of appraisal and reverence for fiber artists.

Instead, skilled sewers, master weavers, and other fabric enthusiasts have had to fight against the view that craft is an inherently lesser form of creativity. A simple, homely handicraft rather than a realm for the imaginative and radically curious. This is a view influenced and perpetuated by an art world that mostly favored the accomplishments of male artists over those of women. The first wave of fiber art resurgence in the 1960s, tightly interwoven with the counter-cultural movement, sought to challenge these views.

As the decades rolled on, we’ve continued to see an exciting shift thanks to the persistent work of artists such as Louise Bourgeois, who unapologetically wields her needle and thread. And now, partly due to the mass uptake of fiber arts as a hobby during pandemic lockdowns, the art world has no choice but to recognize the power and potential of fiber art.

The Storytelling Power of Quilts

“Some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced.”

Most wouldn’t guess this quote describes quilts made of recycled scraps—a craft born from necessity rather than any lofty artistic aspiration. But, this is in fact what The New York Times declared of the first major exhibition of Gee’s Bend quilts in 2002 at Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts. The Gee’s Bend quilting collective was also behind Oscar-winning filmmaker and musician Questlove’s famous 2022 Met Gala jacket.

Questlove’s Met Gala jacket, a Greg Lauren design made in partnership with Gee's Bend Quilters

We’re so thrilled that fifth-generation quilter Loretta and her sister-in-law Marlene are part of the VAWAA family. Their unabashedly colorful and expressively abstract hand-stitched creations never cease to amaze, bringing a complex geometry to life. Learning about this quilting tradition, dating back to the 1800s only heightens the beauty of each piece, expanding our understanding of art.

Loretta’s ancestral lineage directly traces back to Dinah Miller, one of the first enslaved people to arrive in Gee’s Bend, Alabama. Life under land and plantation owner, Joseph Gee, was unimaginably harsh. To cope with the cold in unheated shacks, women collected strips of cloth and turned them into quilts.

Loretta constructing a denim based quilt on the porch

Their sewing methods were improvisational and they approached design with influences from both African and Native American textile patterns. Eventually, the practice took on a life of its own, and the area became known for an abundance of unique hand-stitched collages. Gee’s Bend quilts are practical warm blankets, as well as powerful expressions of the human spirit. Loretta likens the process of creating quilts to therapy. Whenever she feels depressed she “runs for [her] needle and thread” instead of a prescription, she says.

Marlene between two quilts

Heavily embedded in the stories and lives of black women, this art form has faced challenges in getting its ingenuity recognized. Many of the same social issues we grapple with will also be replicated in the arts. That first exhibition of the Gee’s Bend quilts in Houston didn’t happen without grumbles from members of the board that other artists were more relevant and deserving.

VAWAA art apprentice Jennifer shared that despite majoring in art, she’d never been taught about the prolific collective in her studies of American art. After her VAWAA with Loretta and Marlene, she reflected this: “One of my focuses is challenging the established views of what makes ‘fine art’ vs. what is considered craft and/or traditional ‘women's work’. Learning directly from Gee's Bend quilters reaffirmed my belief that stitching cloth is as much of a ‘high art’ as putting paint on a canvas.”

Jennifer and the ladies of Gee’s Bend celebrating the finished product

Being able to stay in Gee’s Bend and learn the tradition directly from two of its masters is opening the minds of many. “My mom got into quilting about 5 years ago and I couldn't really understand her enthusiasm,” another VAWAA apprentice, Tracey, confessed. “Most quilts I had seen looked like ‘old dead white lady quilts.’ I'd never seen a quilt done outside of the typical Eurocentric fashion, so she sent me an article about Gee's Bend (5 years ago!) and I was obsessed.”

A Riotous Revival of Colombian Aesthetics

Historically, Western society has labeled sewing and embroidery as an appropriate hobby for genteel ladies, while high sewing and haute couture have largely been male occupations.

The father of haute couture—Charles Frederick Worth—was a pioneering Englishman who designed for royalty. He debuted his first fashion house, House of Worth, in the 1800s. Though several women have made their mark on the fashion world, to this day, men still occupy most senior positions in fashion. Only 40% of board members are women and a mere 10% are people from minority ethnic backgrounds.

One of our newest VAWAA artists Ana Maria, traveled from Colombia to London to hone her sewing skills. There, she ended up studying with prestigious fashion houses such as Alexander Mcqueen and the British royal family’s embroidery house, Hand & Locke. But despite the high status, Ana Maria felt that the next step in her creative journey lay back home in Colombia.

Returning with all the techniques she’d learned, as well as invaluable business insights, Ana Maria began collaborating with traditional Colombian artisans. The result has been an ultra-vibrant array of garments that uniquely reflect the artists’ Latin American heritage.

Close-up of impressive embroidery mimicking feathers

One dimension of that heritage is magical realism, which has roots in Colombia due to the work of writers such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez. When you take in the landscape, so rich in biodiversity it feels close to fantastical, it’s not hard to see why. Ana Maria’s embroidery is infused with this kind of earthly magic; from the native birds and their luminous feathers to the superabundant flora and fauna that spreads all over her jackets and suits.

A close-up of Ana Maria’s work; her wearing one of her jackets in the studio

Sewing is a global craft. And due to their functional value for societies the world over, fiber arts are seamlessly interwoven with cultural expression. They’re tactile—but they also bring the inner worlds of people from distant lands close to touch.

Ana Maria embroiders with such finesse that she can vary textures, tones, and colors while making them flow with ease. It’s emblematic of her personality, life, and routine. When Olga went on her VAWAA with Ana Maria, she discovered that “understanding the life of an artist is more relevant than taking formal training in a specific subject.”

Looking at the power and boldness of this embroidery work, it’s odd to confine this craft simply as a demure hobby for women. By not only perfecting her technical skills but also embracing her own traditions and following her passion for her homeland, Ana Maria is creating her own space in the world of fiber art.

One of her embroidered landscapes

High Fiber Art for the Home

The renewed interest in fiber arts that arose during the pandemic saw not only knitting, crocheting, and sewing rise but also the more niche fiber art form, rug tufting. Unlike the other categories, which largely focused on clothes-making, this particular resurgence honored the indoor space we find ourselves bound to—our nests.

In the arts and crafts movement of the 19th century, key influence William Morris said, “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” It was a movement that sought to balance the effects of the Industrial Revolution with greater awareness of the importance of craftsmanship and reverence for the arts.

Now, we see a similar tug-of-war happening with the rise of digital technology, yet another revolution. With greater dependence on technology, we seek out slower forms of expression and connection. As Morris reminds us, it begins in the home, with what we choose to surround ourselves with. Rug tufting not only presents itself as a deeply immersive and satisfying activity, but the final product also brings color and texture to the home.

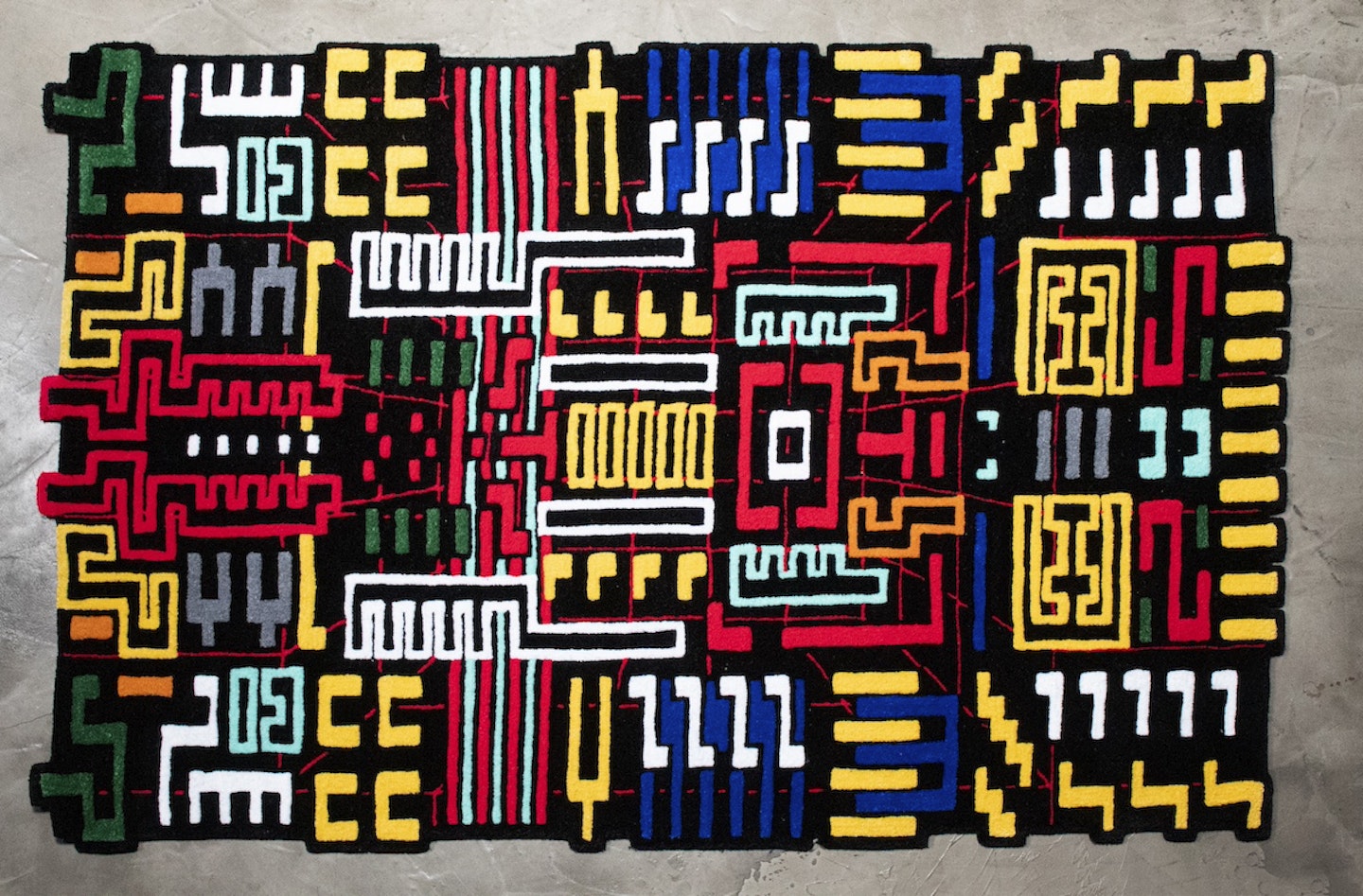

A masterpiece by Pablo and Trini

VAWAA multidisciplinary artists Pablo and Trini in Sevilla, Spain are taking this medium to new heights. Yes, their tufted rugs are bright and dynamic. They captivate our attention and delight our visual senses. But Pablo and Trini also dig deep into art history and use powerful symbolism and motifs to create their designs. Their process of creation is meticulous and innovative, uniting both traditional handwork and machinery.

As their curiosity and imagination elevate the craft to create new and exciting forms of art, we have to consider how their rugs would affect us in the home. Or rather, how their entire approach to craft could infuse the spaces we live and grow in. Pablo and Trini teach art apprentices how to create something physical and tangible, a work of art that will adorn their most beloved space. But they will also share their inspirations, such as their unending desire to explore dreamlike and parallel universes, showing them how to infuse dreams into the process.

Trini creating an outline

Fiber artists inspire us to imagine a more colorful, enriched day-to-day experience. As they are also craft masters, recognizing themselves in an interwoven chain of practitioners, they have the wisdom to show us step-by-step how to turn inspiration into beautiful everyday items. When we demote craft as a lesser form of art, rather than seeking the confluence between the two, we only limit ourselves. Thanks to these artists bravely swimming between these two spheres, a portal to a brighter more creative world is easier to access.

Written by Kat Odina Ali

Explore all mini-apprenticeships, and be sure to come say hey on Instagram. For more stories, tips, and new artist updates, subscribe here.